Hannes Wessels

Hannes Wessels

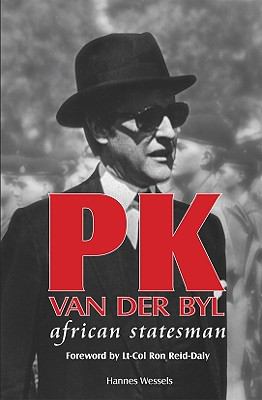

PK van der Byl, African Statesman

Johannesburg: 30º South Publishers, 2010

Margot Metroland

If you need a useful and practical hero in the field of race politics and statecraft, you might take a good look at a colorful and headstrong eccentric named Pieter Kenyon Fleming-Voltelyn van der Byl (1923-1999).

When it comes to the story of independent Rhodesia, most people only remember Prime Minister Ian Douglas Smith. But statesman-soldier PK (as he was always known) was the truly steadfast and remarkable figure in that saga. Without him, Rhodesia might well have folded its tent in four years, instead of surviving for a battered and beleaguered fourteen. Had there been a hundred PK’s, Rhodesia might well have gone on forever.

Born into one of the oldest Cape Dutch families in South Africa, PK served in the Second World War (British Army, 7th Hussars, in Italy and Austria) and then read law at Pembroke College, Cambridge. After which he became, of all things, a tobacco planter in what was then known as Southern Rhodesia. Gradually he entered politics, becoming active in the new pro-white-rule Rhodesian Front party. In 1965 Harold Wilson’s Labour government announced their intent to turn Rhodesia into yet another disastrous black-run satrapy, and never mind the recent examples of Gold Coast (Ghana), the Belgian Congo, Kenya, and Northern Rhodesia (Zambia). PK was second to none in his insistence that Rhodesia cut its ties to Britain and go its own way.

But first, in September, Ian Smith went to London to plead with Harold Wilson. Wilson and the government were intransigent. Wilson threatened military force, and 40 Labour MPs were calling for immediate invasion. Nor were many Tory MPs sympathetic. Even the Archbishop of Canterbury got in on the act, demanding that the RAF bomb Salisbury, Rhodesia’s capital.

And that’s how we got to the Unilateral Declaration of Independence, or UDI, signed in Salisbury, Rhodesia by Prime Minister Ian Smith and his government on November 11, 1965, PK van der Byl’s 42nd birthday.

For the next 14 years PK remained the most passionate hard-liner in the government. Intimating that Smith was irresolute and maybe too willing to compromise, PK let it be known that he’d eagerly take over if he ever detected “the least whiff of surrender.” Beginning as a lowly deputy minister of information, PK soon became full minister, later was given the ministries of Defence and Foreign Affairs. Throughout his tenure he was determined to control the national narrative, imposing firm censorship of anti-UDI newspapers and journalists, and even deported visiting British journalists for negative coverage. Young Max Hastings came to Salisbury to write sneeringly in the Evening Standard that Smith and PK “would have seemed ludicrous figures, had they not possessed the power of life and death over millions of people.” Max got the boot.[1] So did other writers, academics and politicians who came to Rhodesia on a hate mission.

PK loved to visit the forces in the bush (SAS, Rhodesian Light Infantry, Rhodesian African Rifles) and share in their terrorist-hunting. He dressed for the occasion and was a sight to see. A group captain recalls PK’s arrival one day in the Zambezi region (NW Rhodesia):

[H]is arrival…for his helicopter flight to the site was quite an eye-opener because his dress was so appalling. Below his Australian bush hat he wore a pink shirt with bright blue tie, khaki shorts with black belt, short blue socks and ‘vellies’ (veldskoene, lit. bush shoes). His strange dress in the bush was often discussed. I honestly think he did this from time to time for the shock effect. He knew the Zambezi Valley like the back of his hand, having walked it extensively on his hunting expeditions.When the RLI and SAS got to know him better, PK became very popular with the soldiers. His ridiculous accent appealed to them just as much as his strange dress.He often requested to be taken on patrol so he could “shoot a terrorist” but asked that care be taken not to get him “lawst.” (pp. 143-144)

Here is some real insight into the PK mystique. Tall and striking to begin with, he cultivated further attention (or authority) through sartorial elegance or oddness. And his drawling accent was from another era entirely, something one might associate with an elderly palace courtier, who pronounces “house” as hice and “girl” as (hard g) gel. An affectation, many people assumed. At Cambridge in the ’40s they called him the Piccadilly Dutchman.[2]

PK out in the bush.

Speaking of which, South African Prime Minister John Vorster couldn’t stand him (“that dreadful man”), and told Ian Smith never to bring PK along when Smith and Vorster met at rugby matches for quasi-unofficial strategy discussions. To Vorster, PK was a traitor to his people, a old-stock Boer who affected a phony British accent and “imperial mannerisms.”

Old Cape Dutch he certainly was, at least on his father’s side, but he was scarcely a Boer. The van der Byls had been Anglicized since the mid-1800s, and sided with the Crown during the Boer Wars. PK’s father “Major Piet,” another soldier-statesman, had been a minister in General Smuts’s cabinet in Pretoria during the 1940s. Moreover, PK’s mother was Scottish, daughter of an Army physician and Lieutenant Colonel. With this sort of pedigree, you can easily see PK shaping up into a cross between Harry Flashman and something out of P. G. Wodehouse’s Drones Club. (PK’s London club was in fact White’s.)

Further to PK’s character, a succinct description is found at the start of PK van der Byl, African Statesman, in the Foreword by longtime friend Lieutenant-Colonel Ron Reid-Daly:

My early impression of PK was…most unfavourable, because at first sight he appeared to have all the characteristics of a chinless Pom. I remember wondering how Ian Smith, a down-to-earth Rhodesian, had seen fit to accept him into his party. ***[B]ut I was soon highly impressed by him. Unlike many of the more pedestrian types in the military and political hierarchy, PK was focused and absolutely determined to do whatever it took to win the war… Vilified in the international press as an unrepentant racist, he was totally committed to the welfare of his black troops.***

In the light of history there is little doubt in my mind that South African Prime Minister John Vorster, in his misguided effort to win favours from African leaders, scuppered Rhodesia’s chance of survival, hastened the collapse of white rule in Africa and altered the course of continental history when he forced Ian Smith to dismiss PK van der Byl as Minister of Defence. (pp. 6-7)

“Get rid of van der Byl or I’m turning off the tap,” Vorster said in a 1976 phone call to Smith, according to PK. PK remained in the cabinet as foreign minister, but that was hardly more than a title, inasmuch as Rhodesia was an international pariah, maintaining diplomatic relations only with South Africa…which didn’t want to talk to Foreign Minister van der Byl!

In the mid-70s, Marxist hegemony in Africa moved at a galloping pace. A Leftist military coup in Lisbon meant that once-friendly Portugal now broke relations with Rhodesia, and condoned the Soviet-backed black nationalists in Mozambique (on Rhodesia’s east and north) and in Angola. Rhodesia was now nearly encircled by hostile governments—except for South Africa, where John Vorster was playing a “please eat me last” game, hoping to buy time by gradually sacrificing Rhodesia.

There were other, subtler international factors that disadvantaged Rhodesia as the 1970s progressed. Though frozen out of official diplomatic intercourse, the country had maintained useful contacts with senior intelligence in France during the De Gaulle years (enabling exports of Rhodesian agricultural products), but these became less useful with changes of government. Ian Smith nurtured some warm, promising relations with British ministers early in the Heath years (notably Foreign Secretary and former Prime Minister Alec Douglas-Home). Instead of “black rule” or “majority rule,” Whitehall in 1971 agreed to pursue the idea of “responsible rule,” and a friendly British-Rhodesian agreement seemed to be in the offing.

It emerged Heath sunk the Rhodesia settlement in exchange for Liberal support for UK entry into the European Common Market. Liberal leader Jeremy ‘Bomber’ Thorpe had long sought Rhodesia’s fall and Heath traded this irresistible scrap. Thorpe considered white Rhodesians homophobic and an embarrassing relic of a shameful imperial past. (p. 160) [3]

Rhodesia ceased to be in 1979, with the so-called Lancaster House Agreement in London. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher didn’t want to drag this tiresome Rhodesia legacy any further into her premiership, and so she forced an agreement to accept a new “Zimbabwe-Rhodesia” government under the black Bishop Muzorewa.

But even that effort was a failure, as the Muzorewa regime was regarded by most governments (including Jimmy Carter’s in America) as merely a puppet of Ian Smith and company. The following year Robert Mugabe took power.

For the next few years, PK sat in the Zimbabwe parliament. There were ten reserved “white” seats in the early years, per agreement. Otherwise he and his new wife Princess Charlotte, granddaughter of the last Habsburg Emperor Karl I, retreated to the elegant van der Byl family estate in the Western Cape (South Africa). They had three sons.

Wedding in Austria, August 1979.

I first bought this book ten years ago. But in coming back to it now, I realize I mainly just delved into the “hot parts,” i.e., the UDI, the collapse of Rhodesia in the latter 1970s, and the extensive photo section. This time around, I was impressed by the densely detailed history of southern Africa from the 1600s to 1800s, and by the geopolitical background to the UDI. Ian Smith and PK and their colleagues in the Rhodesian Front clearly perceived the Communist effort to wreck stable governments in Africa in the early 1960s, using the pretexts of anti-colonialism and black rule.

My paperbound copy of the book cost me about $20. You can now buy the same edition for about $199. But not to worry. There is finally a Kindle version for only $6.99.

Notes

[1] Though according to author Wessels, Max Hastings visited numerous times, “masquerading as a Rhodesiaphile hunter-fisherman, [and] repaid endless hospitality with vitriolic scorn”:

Like most of my colleagues I reported from Rhodesia in an almost permanent state of rage. We saw a smug, ruthless white minority, beer guts contained with difficulty inside blazers with RAF crests, proclaiming themselves the guardians of civilization in the heart of Africa. (p. 127)

[2] On a bawdier angle, P.K. was called “Tripod” by his fellow tobacco farmers, for his rumored sexual prowess.

[3] While author Wessels may be guessing right, it’s more likely Mr. Thorpe was just being bien-pensant. “Homophobic” is an anachronism here as it did not enter popular parlance until about 1990.