Rolleiflex selfie of Philip Larkin and Monica Jones in Paignton, Devon, circa 1957. (From Andrew Motion’s Philip Larkin: A Writer’s Life, 1993.)

He’s been dead for 37 years, but the Philip Larkin literary industry keeps burbling along, fueled by a seemingly inexhaustible supply of titillating tales, spicy correspondence, and uncollected reviews, diary scraps and photographs. He’s been the subject of stage plays and TV docudramas, countless critical essays and monographs…and no end in sight.

Just last year we were treated to a new memoir about Larkin and Monica Jones, his longtime colleague and—inamorata? soulmate? caretaker?

“Philip Larkin’s Muse, Monica Jones, Revealed as a Racist” screamed one typical headline. As clickbait this subject was so tasty that The Times (London) reviewed the book three times.

Philip Larkin was vilified after his death for his racism, misogyny and philandering. Now the bigotry of his muse has been exposed in a book…

A ditty hitherto attributed to Larkin read: “Prison for the strikers / Bring back the cat / Kick out the n*****s / How about that?” Any idea that this was satirical is tempered by her once telling Sutherland she planned to vote for the British National Party.

Antisemitism appears to have been Jones’s primary racial preoccupation. A letter she wrote in 1960 about a dinner referred to “a young Y*d publisher” and she later described a female philosopher as a “mincing lisping foreign Jew dwarf”.

Asterisks courtesy The Times. [1]

This is a good example of how far afield the literary tabloid-sensationalism has crept with regard to Larkin. Back in the 1990s we had exposés of Larkin’s odd family and odder love affairs. A decade later we were treated to Larkin’s scurrilous correspondence with Kingsley Amis and others. (Seems they both liked jazz…and porn.) And now apparently we’ve moved into the outer suburbs of the subject, where we trawl through the mean-girl thoughts of the poet’s girlfriends.

Ironically the author of this book quoted above, John Sutherland, was for many years a friend of both Philip Larkin and Monica Jones. Sutherland explains that he originally intended the book to rehabilitate Monica’s reputation, but somehow it just didn’t come out sympathetically when he set it down on paper. And Sutherland couldn’t resist setting it all down. It was too saucy and scandalous, and that stuff always sells when Larkin’s involved. [2]

So when did this Larkin boom begin? Loosely speaking, Philip Larkin first came onto most people’s radar during the Margaret Thatcher era. Meeting him at a dinner in 1982, the Prime Minister gushed like a schoolgirl about how he was her favorite poet. Whereupon a dubious Larkin asked which of his poems was her favorite! So the PM quickly misquoted a line from one of his poems, the title to which she did not recall.

This misquote endlessly impressed Larkin. It told him that Mrs. Thatcher was truly searching old memory banks, and not reciting something she’d learned just that afternoon. [3]

Two years later Poet Laureate John Betjeman passed away, and Mrs. Thatcher offered the post to Philip Larkin. But Larkin didn’t want to be Poet Laureate. No, he preferred his relative obscurity as librarian at the University of Hull, on the bracing North Sea. He didn’t want to have to go on the telly or write vers d’occasion on demand. No doubt he noticed that Betjeman’s own late-career stuff was pretty awful. Besides, Larkin thought he had become old and fat, and figured he was going to die soon. As indeed he did, of throat cancer, at the end of 1985.

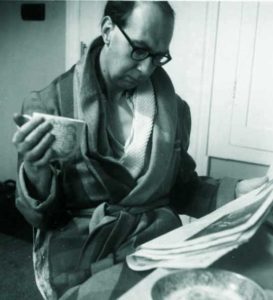

Selfie with newspaper, 1957.

The first version of his Collected Poems came out in 1988, and then Selected Letters in 1992. But the interest in Larkin really took off in early 1993, when fellow poet Andrew Motion published Philip Larkin: A Writer’s Life, a fat, sympathetic, but perhaps too revelatory biography. [4] Motion’s book was generously illustrated with photographs, and invited hoots of mockery in the London media when in March 1993 some newspapers reviewed it alongside lavish photo spreads of Larkin and his various girlfriends and other companions. Larkin at Oxford, Larkin in Devon, Larkin in Hull, Larkin in the Channel Islands. It was as though some anonymous photographer just followed him around for much of his life.

Much later we learned that the photographer was often Larkin himself. He was an avid taker of selfies a half-century or more before Instagram. Usually his self-portraits were medium-format black-and-whites, done in available light with a Rolleiflex atop a tripod. He took them using the timer setting or maybe a shutter-release cable. [5]

I had a friend named Simon Hoggart who was among other things the “Parliamentary sketch writer” (a kind of gossip columnist) for The Guardian. Simon told me that the journo folks in Clerkenwell and Westminster were all a-twitter about a campy photo of a simpering, sandaled Larkin in 1955, with his hands clasped upon a knee. (“Did you see that picture of him at the beach?”) Andrew Motion says the picture was taken by Monica Jones during a holiday on Sark, and maybe it was. I say it has all the appearance of a jokey Larkin selfie. [6]

The notorious “camp” photo on Sark, 1955. Or 1957? Either a selfie or by Monica Jones. (From Andrew Motion’s Philip Larkin: A Writer’s Life, 1993.)

A bigger subject of wide-eyed wonder in 1993 was Motion’s description of Larkin’s father. Sydney Larkin was City Treasurer of Coventry in the 1920s, 30s, 40s. We’re told he had a great admiration for Nazi Germany, and was even a pen-pal of Hjalmar Horace Greeley Schacht, the German economics minister. According to a onetime Hull professor who was Larkin’s drinking companion,

Sydney had been “an ardent follower of the Nazis and attended several Nuremberg rallies during the 1930s; he even had a statue of Hitler on the mantelpiece…which at the touch of a button leapt into a Nazi salute”… As late as 1939, Sydney had Nazi regalia decorating his office in City Hall, and when war was declared he was ordered by the Town Clerk to remove it. … He didn’t even change his tune when Coventry was blitzed in November 1940. Instead, he congratulated himself on his foresight in having ordered one thousand cardboard coffins the previous year, and continued to praise “efficient German administration,” while disparaging Churchill—who had, he thought, “the face of a criminal in the dock.” [7]

Classic, priceless, hilarious stuff. But how much of it to believe? Back in March 1993 I think we believed most of it. This was still the age of Alan Clark, the far-Right Tory diarist, MP, and sometime Thatcher government minister, who once responded to a taunt by saying, “I am not a fascist. Fascists are shopkeepers. I am a Nazi.” The story of Larkin’s father was edgy, but not all that outré. It was rather chic, in fact, to have had Blackshirt tendencies.

But while some of these stories about Sydney seem to be true (they’ve been corroborated), others are most likely romantic, imaginative embellishment on the part of Philip Larkin. Because right after telling us about Nuremberg, and the push-button Hitler doll, and the excellent deal on cardboard coffins, biographer Andrew Motion pretty much implies that these stories came mainly from Larkin himself, back in the 1950s and 60s:

Sydney Larkin was generous to his son, and often indulged him, but nevertheless strutted through his early life with a singular arrogance. He was intolerant to the point of perversity, contemptuous of women, careless of other people’s feelings or fates, yet at the same time excitingly intellectual, inspirationally quick-witted and (at least in the matter of books) unpredictably catholic in his tastes. Everything Larkin disliked or feared in his father was matched by something he found impressive or enviable… As the first half of Larkin’s childhood dripped away, the mixture of feelings he had for his family gradually thickened. By early adolescence…it had turned into rage. “Please believe me,” he told his first important friend, “when I say that half my days are spent in black, surging, twitching, boiling HATE!!!” [8]

The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree, and Larkin knew it. He was very much his father’s boy, and was both embarrassed and exalted by that.

Herein lies, I submit, the core of the Larkin genius. It’s a depressive, self-loathing attitude that nevertheless focuses hard on loathing of self, family, and present surroundings, and yields painful and satirical insights. Bad selfies, sad selfies, good selfies, but selfies nevertheless.

Notes

[1] “Philip Larkin’s Muse, Monica Jones, Revealed as a Racist,” The Sunday Times, London. April 11, 2021. [2] John Sutherland, Monica Jones, Philip Larkin and Me: Her Life and Long Loves. London: W&N, 2021. [3] The poem is a thorny thing called “Deceptions,” about a ruined girl and her rapist. It wasn’t one of Larkin’s better known poems in 1982, but has become so since, thanks to Mrs. Thatcher’s mangled recitation: “All afternoon her mind lay open like a drawer of knives.” [4] Andrew Motion, Philip Larkin: A Writer’s Life. London: Faber & Faber, 1993. [5] Many of his photographs are collected, and his selfie technique explained, in The Importance of Elsewhere: Philip Larkin’s Photographs, edited by Richard Bradford. London: Frances Lincoln, 2015. [6] Obscure literary trivia: Around the same time Philip Larkin and Monica Jones holidayed on Sark—one of the smaller Channel Islands—the writer Bill Hopkins visited the island. Bill used it as a setting for his legendary/notorious novel The Divine and the Decay. Did Larkin and Hopkins ever cross paths, there or elsewhere? [7] Motion, Philip Larkin, 12. [8] Motion, Philip Larkin, 13.