Paul Fussell

Paul Fussell

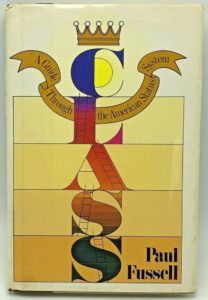

Class: A Guide Through the American Class System

New York: Summit Books, 1983 (First edition—many since)

Written in 1980-82 and published in 1983, Paul Fussell’s Class: A Guide Through the American Status System is one of those rare books that most literate people seem to have heard of, say they want to read if they haven’t, and have fierce opinions about whether they’ve read it or not. I see this last aspect frequently on social media. When a few people were discussing it on Twitter, one of them described it dismissively as “an old book, it’s mostly just about white people.”

My Twitter friend was trying to be helpful, I think. He wanted to disabuse us of any possible misapprehension that Prof. Fussell’s book was a treatise on urban socioeconomics and ethnicities. Because nowadays some people do in fact use “class” as a euphemism for income or race. If you’re Joe Biden, for instance, you might use “lower class,” “poor people,” and “black folks” pretty much interchangeably.

But I wanted to Twitter-shout in all caps: OF COURSE the book is mostly just about white people! Otherwise it would be called Race, or something. Even in a mock-sociology book like this one, discussion of class distinctions only makes sense within the context of a fairly homogeneous population. The same way the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show in New York does not permit you to enter your cat or ferret. Because it’s all about dogs. Likewise Class does not examine the social habits of the Vietnamese community in Westminster, California. Because it’s not about Vietnamese.

Besides homogeneity, it also helps if you restrict your examination of class markers to a fairly tight geographical area. This is why this genre of book is so much more persistent and successful in Great Britain than in America. If you’re at Waterstone’s and you see a cartoon book about Social Stereotypes (the Telegraph Magazine actually had a long-running series by that name), you automatically know it’s going to be about upper-middle-class people in Home Counties England. But America is too vast for that sort of thing. The lower-middles don’t know the upper-middles even exist (or they think it’s all about money). Americans don’t share that many identifiable social markers and stereotypes. The closest thing perhaps is the tedious caricature of Flyover Country so beloved of the Washington Post and other Leftist organs. You know—obese people in red MAGA hats who go to Walmart.

Fussell dispensed almost entirely with Flyover Country, limiting his book’s scope mainly to the Middle Atlantic and New England region, with the occasional sneer at Texas, Hawaii, and fat people at the Minnesota State Fair. Nevertheless his funniest bits are put-downs of what he presents as the horrendous style sense of people out in the boonies. Since the Pasadena-born Fussell spent most of his professorial career in central New Jersey and Philadelphia, and traveled mostly to England and Italy, I have to wonder how he did field work on such grotesqueries as the “prole hat” you see below. My guess is that he didn’t, really. He just glimpsed them in some airport concourse, and conjured up a cockeyed explanation. But what he says is all the funnier for that:

Proles take to visor caps instinctively, which accounts for the vast popularity among them of what we must simply call the prole cap. This is the “baseball” cap made largely of plastic meshwork in primary colors (red, blue, yellow) with, in the rear, an open space crossed by a strap for self-adjustment: “One Size Fits all [Proles].” Regardless of the precise style of the prole cap, it seems crucial that it be ugly. It’s the male equivalent of the purple acrylic slacks worn by the prole’s wife… The little strap at the rear is the significant prole feature, because it demeans the buyer and user, making him do the work formerly thought the obligation of the seller, who used to have to stock numerous sizes… To achieve even greater ugliness, the prole will sometimes wear his cap back to front. This places the strap in full view transecting the wearer’s forehead, as if pride in the one-size-fits-all gadget were motivating him to display the cap’s “technology” and his own command of it.

This is Fussell at his delightful snarkiest. Nobody had a name for this pictured headgear before he named it the prole cap. Neither did anyone suggest the rationale for turning it backside-to was to show off the adjusto-strap technology. Of course this fanciful explanation isn’t quite true. It was skateboarders who started the fad of turning the visor to the rear, sometime in the 1970s. Wearing the cap hind-side-to lowered the drag coefficient, or whatever, and allowed for unobstructed vision, which might be useful when doing a 360º loop. And skateboarders didn’t wear high-profile mesh numbers like Farmer Yokel here (that would defeat the purpose) but rather tight-fitting low-profile caps, almost like those skimpy things that Italian cyclists wear. You’d have to be as old as Steve Buscemi or me to recall such sartorial trivia. As the good Professor was then in his fifties he missed it entirely.

When I attempt to gather up my favorite Fussell snippets, I find that they generally pertain to clothing and accessories:

Only six things can be made of black leather without causing class damage to the owner: belts, shoes, handbags, gloves, camera cases, and dog leashes.

Jewelry is another instant class-lowerer, like the enameled little Old Glory lapel pins worn by the insane and by cynical politicians working backward districts.

Today hats, because of their rarity, present an easier class problem than neckties. Since the felt fedora went out, upper-middle-class people can wear only the equivalent of parody hats — “Russian” fur, the L. L. Bean “Irish” tweed hat favored by Senator Pat Moynihan, or the floppy white fishing or tennis hat popular among the top classes despite its being favored by Franklin D. Roosevelt.

[Displaying your shirt collar] spread out over the jacket collar, unless you’re a member of the Israeli Knesset or teach at the Hebrew University, is flagrantly middle-class or prole—and may be even then.

Some of his best lines are still funny but very dated:

All synthetic fibers are prole, partly because they’re cheaper than natural ones, partly because they’re not archaic, and partly because they’re entirely uniform and hence boring—you’ll never find a bit of straw or sheep excrement woven into an acrylic sweater.

Smiling is a class indicator—that is, not doing a lot of it. On the street, you’ll notice that prole women smile more, and smile wider, than those of the middle and upper classes.

It’s the three prole classes that get fat: fast food and beer are two of the causes, but anxiety about slipping down a rung, resulting in nervous overeating, plays its part too, especially among high proles. Proles can rationalize their fat as an announcement of steady wages and the ability to eat out often: even “Going Out for Breakfast” is a thinkable operation for proles, if we believe they respond to the McDonald’s TV ads the way they’re conditioned to.

For me, these three are period pieces. Synthetics still meant doubleknit polyester leisure suits for men and purple polyester pantsuits for women, not tech fabrics, Gore-Tex, Ultrasuede. And I can’t imagine where Fussell saw gangs of smiling proles waddling down the pavement and gulping breakfast at McDonald’s. Perhaps my airport-concourse theory explains all. The 1970s were the decade when people stopped dressing like the Mad Men cast when they went to the airport. They started to arrive in sweatshirts and ballcaps, and by the 1980s fashion-forward frequent flyers were doing it in two-piece nylon tracksuits, with a canvas duffelbag carry-on. The new slovenliness was perhaps connected with the fact that airlines had begun to hire stewardesses who were gay males, 55-year-old grandmothers, and colored folk. Before that, stews had a distinct “brand,” enforced by tape measures, girdle checks and uniform makeup. From what the stews told me, Pan Am gals usually had dark hair, while United mainly went for blondes. But then smart appearance no longer mattered, esprit took a dive, and the public started to board the Buses of the Air wearing any old thing. A slippery slope.

For me, these three are period pieces. Synthetics still meant doubleknit polyester leisure suits for men and purple polyester pantsuits for women, not tech fabrics, Gore-Tex, Ultrasuede. And I can’t imagine where Fussell saw gangs of smiling proles waddling down the pavement and gulping breakfast at McDonald’s. Perhaps my airport-concourse theory explains all. The 1970s were the decade when people stopped dressing like the Mad Men cast when they went to the airport. They started to arrive in sweatshirts and ballcaps, and by the 1980s fashion-forward frequent flyers were doing it in two-piece nylon tracksuits, with a canvas duffelbag carry-on. The new slovenliness was perhaps connected with the fact that airlines had begun to hire stewardesses who were gay males, 55-year-old grandmothers, and colored folk. Before that, stews had a distinct “brand,” enforced by tape measures, girdle checks and uniform makeup. From what the stews told me, Pan Am gals usually had dark hair, while United mainly went for blondes. But then smart appearance no longer mattered, esprit took a dive, and the public started to board the Buses of the Air wearing any old thing. A slippery slope.

As a professor emeritus, Fussell missed the casual-Friday/casual-everyday abandonment of office dress codes circa 1995-2000, but I suspect he could have diagnosed the problem. It was a move spearheaded by tech geeks who viewed office life as a perennial cold war between Techies/Creatives and The Suits. Fussell muses upon “the social-class problems of engineers, uncertain always where they fit, whether with boss or worker, management or labor, the world of headwork, or the world of handwork.” When The Suits were top dog in Corporate Land, they enforced a dress code originally based on the uniform of counting-house clerks and bankers, circa 1820. But then tech engineers became ascendant, and they preferred a livery that was a mashup of golf wear and something you’d pull on when cleaning the garage. And so was born the Age of the Slob.

Like that other pungent snob, Wilmot Robertson, Fussell was a dab hand at coining memorable phrases to describe troublesome social phenomena. Given his fear and loathing of prole culture, it’s appropriate that his biggest contribution to the language is “Prole Drift.” It describes widespread class sinking, “the tendency in advanced industrialized societies for everything inexorably to become proletarianized.” Many of Fussell’s examples of prole drift are biased and cranky, such as the proliferation of newspaper horoscope columns, and a fortune-teller ad that ran in The New Republic in 1982. But then there astute, far-reaching complaints, such as the gradual “disappearance of service and amenity, the virtue universality of ‘self-service'”:

Self-service is ipso facto prole. Proles like it because it minimizes the risk of social contact with people who might patronize or humiliate them. All right for them, but because of prole drift we’re all obliged to act as if we were hangdog no-accounts.

Coming out in late 1983, Class appeared at almost the same time as the unspeakable Official Yuppie Handbook, which I spoke of a while back. Unlike that sad Yuppie book Fussell’s Class has never gone out of print or slithered off into complete irrelevancy or become a nostalgia curio. It grew out of a shrewd, witty piece that Fussell wrote for The New Republic a few years earlier. (“A Dirge for Social Climbers,” July 19, 1980.) So when you open Class, you’re meeting a mindset that really jelled around 1978 or 1979. This explains a few of the book’s obsessions, and also its design and title. You see, in 1979 the English writer Jilly Cooper had published a book of similar heft, topic, and line drawings, also called Class (subtitled A View from Middle England). The resemblance is of form rather than substance, since the Cooper book chatters on about Eton ties and Clubland and Hooray Harrys—things that have no meaningful parallels in America, or at least no parallels that the average reader would be conversant with. Cooper’s Class moreover echoes earlier humor books on the theme of class and status, most notably Noblesse Oblige (by Nancy Mitford, Evelyn Waugh, Osbert Lancaster, et al.) and Social Types by Ronald Searle; both of them from 1955.

These English writers all illustrated class distinctions by caricaturing familiar types of the upper and upper-middle class (familiar, that is, to their peers and neighbors). Paul Fussell couldn’t do anything like that because he wanted to draw a bigger picture, and there just aren’t enough Americans with shared history and biases. Or rather there are, but we’re mostly in little particularist tidepools. If you try depict the common stereotypes you know, you end up with something like Flannery O’Connor or John P. Marquand: an illustration of a somewhat exotic community rather than a broad-based, shared class structure. So Fussell, like Thorstein Veblen and Dwight MacDonald before him, tries to construct a general theory of American class and status. He posits an awkward, dubious taxonomy of nine distinct classes, beginning with “Top-Out-of-Sight” (so upper-upper you’ll never see them or their houses) and ending with “Bottom-Out-of-Sight,” who rank below “Destitute” and are probably institutionalized someplace. He also gives us an X class, consisting of people who don’t quite fit into any of the other nine: artists, writers, expats . . . probably a lot of the people you know.

In the end Fussell’s class system is a put-on, just an excuse to make fun of the three Prole groups (High, Mid, and Low). Some years after publishing Class, Fussell still had a lot more to say on this score, and so produced a little book called BAD—Or, the Dumbing of America (1991). BAD was pretty bad, just another opportunity for Fussell to have a go at prole pop culture.

Being a lifelong academic, Fussell didn’t really have a good sense of what other classes were about. He saw, or thought he saw, proles at the airport and shopping mall and on TV, but his notion of upper-middle-class people seems to be based on the more worldly, genteel, probably tweedy academics he met in his English departments and at scholarly conferences. Sometimes he just wings it, teases us, makes stuff up.

He informs us, bizarrely, that upper-middle-class Americans often affect an Anglomania and fascination with British royalty. “You meet people whose dinner tables ring not just with passing references to the royal family but with prolonged earnest dissertations about Charles and Lady Di and Margaret Anne and Andrew and Little Prince William.”

Have you ever encountered folks like that? I certainly haven’t, and I doubt such dinners were ever a frequent occurrence for Fussell. I assume such Royal-stans would be sluggards who make a fetish of supermarket tabloids and tabloid TV, or are themselves lower-middle-class Brits in origin, or they’re really Jewish (or maybe all three at once, as has been known to happen); in which case they’re certainly not upper-middle-class Heritage Americans. I’ve known only one American who ever even mentioned the Royals in dinner table conversation, and that was the eldest of the four Koch brothers. (Certainly an Upper, if not actually Top-Out-of-Sight in the Fussell taxonomy.) And Fred Koch didn’t say “Charles and Lady Di,” but correctly referred to them as the Prince of Wales, etc. He was making some brief point about a charitable venture he was affiliated with. Fred was no more than a passing acquaintance of that family. But he did have a recent Christmas card from “Lilibet and Phil.”

Is Fussell just having a big joke with us here, as with his X Class and those enameled Old Glory lapel pins “worn by the insane and by cynical politicians”? That’s a pretty good guess. Fussell himself never took his Class book very seriously and was surprised when people did, or when they were alarmed or offended to the point of sending hate mail—or when they studied it as a vademecum, a literal “Guide Through the American Status System.” As Fussell gleefully admitted in his memoir, Doing Battle (1996):

This was hardly a serious book, for often the presentation was conducted in the comical voice of an excessively earnest, pedantic professor of sociology, accustomed to rigid classifications and pseudo-scientific method.

Whimsically, he supplied Class with an author’s note that went, “In real life, Paul Fussell is Donald T. Regan Professor of English Literature at the University of Pennsylvania,” that being the new English chair to which Fussell was appointed. But when the London paperback edition was being prepared, an editor added a superfluous comma, making the sentence, “In real life Paul Fussell is Donald T. Regan, Professor of English…”

Thus for months, and it’s still happening, I would receive anti-fan mail from England beginning as follows:

Dear Professor Regan,

Your book is so offensive that I quite understand why you feel it necessary to hide your actual identity behind such a ludicrous pseudonym as “Paul Fussell.”